Each month we invite an inspirational or outstanding deaf role model to share their story. From what they’ve learnt, to what they wish they’d have known and their best deaf tips.

Each month we invite an inspirational or outstanding deaf role model to share their story. From what they’ve learnt, to what they wish they’d have known and their best deaf tips.

This month, meet Dr. Joseph Hill – a well-known figure in the American Deaf communities as an academic, a Black Deaf Role model and a leader in diversity and equality. We take great pleasure in introducing Dr. Hill to a wider audience across the world and benefitting from his personal and nuanced perspective.

Find out more about Dr. Hill and his work here.

1. Hi Dr Joseph! Tell us about yourself?

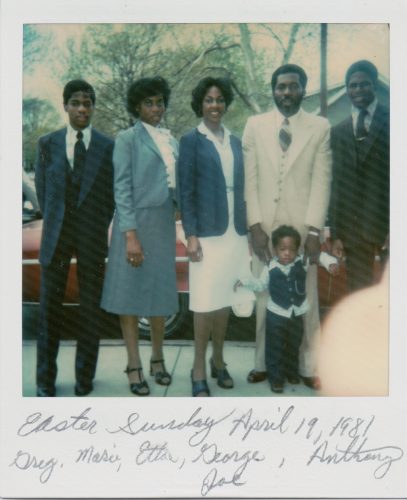

I am Dr. Joseph C. Hill. I am a Black Deaf man from Cincinnati, Ohio and I was raised in a family of 4 deaf and hard of hearing children, 1 hard of hearing mother, and 1 hearing father. In 1997, I graduated from Hughes High School as one of the top 15 and went to Miami University of Ohio to study Systems Analysis which is basically software engineering. After that, I went to graduate school at Gallaudet University in 2002. Now I am an Associate Professor at Rochester Institute of Technology and I work at one of the nine colleges on campus, National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID). My department is American Sign Language and Interpreting Education. I am also an Assistant Dean for Faculty Recruitment and Retention under the NTID Office of Diversity and Inclusion.

I am tasked with supporting NTID’s goals to diversify the faculty, to ensure that the faculty search and hiring is inclusive and equitable, and to identify what keeps the faculty satisfied in term of career development and scholarship support. I am also an Associate Director of the NTID Research Center on Culture and Language in which my Deaf Studies Lab is housed. These are the achievements after graduating with a Ph.D in linguistics at Gallaudet University in 2011. My journey as an academic is not easy and there has been several times I thought about leaving academia altogether, but something keeps me on the path and I am still going. I think I am still going because Black Deaf role models are still not as visible and I want to change that.

2. What is your deaf story?

I was raised in the family of 4 deaf and hard of hearing children, 1 hard of hearing mother, and 1 hearing father. I am the youngest so it started early for me. It may appear that I am from a deaf family but it’s complicated for me to claim the “deaf family” label because my parents didn’t sign and my siblings and I were mainstreamed in a program that emphasized oral communication. Later in our teens, we started signing as our primary communication. My siblings and I always had deaf classmates so we did have connections to the Deaf communities (I use the plural form on purpose as there are different communities of deaf people based on their backgrounds).

My sister is the oldest (we are 15 years apart) and went to NTID so she brought a lot of elements of Deaf Culture to my family. She was very involved in the Deaf community in our town so I got my exposure through her. My brothers had deaf friends as well. I started signing when I was in middle school and got my first interpreter. My identity had slowly shifted from hard of hearing to Deaf as I became more exposed to Deaf culture.

3. What was your experience of education as a deaf person?

I was mainstreamed my entire life like with my 3 deaf and hard of hearing siblings. I never went to a residential school so I didn’t know what I was missing. I thought that mainstreaming was normal for me. I do remember how hard it was for me in elementary school as a deaf kid. I identified myself as hard of hearing because my mother was and the school treated me as such. I could hear with my hearing aids and I could speak, but my voice sounded different no matter what I did. So I did get teased and a few times I was bullied. It didn’t help that I liked boys too and kids picked up on that. Fortunately, I was big and tall for my age so I didn’t experience as much bullying. Just to give you an idea, I was 6 foot tall when I was 11. My height was my survival advantage and my intellectual capacity was another. I do remember that I had a lonely childhood. I was in a deaf program in a public school but the teachers felt that I was too advanced for the program. I think I was in my 3rd or 4th grade. They wanted to move me out and be fully mainstreamed. I didn’t remember what happened, but my mother said that I didn’t want to move out of the program because I would be the only deaf kid in the hearing classroom. My mother fought for me to stay and told them to give me time to get ready. The teachers had to give me extra work to support my learning and I was able to stay with the deaf kids. The school was the only time I could be with my friends. At home, I didn’t really have neighbor friends so I was by myself. My brothers and sister had graduated high school and moved out of the house when I was about 6.

When I was in high school, I was ready to be fully mainstreamed because I wanted to go to college and I knew I needed to maximize every educational opportunity to have a chance to be admitted. I had the interpreters and I had one deaf friend with me in every class. My middle and high school experiences were interesting because the schools were predominantly black and my best friend was a white deaf kid. I didn’t really have a close black friend. In the last two years of high school, I felt like I lost my best friend because he was interested in his girlfriend and football. I didn’t have anyone else to hang out with and the people I called my friends were my teachers and interpreters. I put all of my energy into schoolwork and extracurricular activities so I could go to college.

I was lucky to be enrolled at Miami University of Ohio which is 45 minutes from my hometown. What I didn’t know is that it was considered a public ivy league institution and the student population was more than 90% white. And with the student population of 16,000, only 11 students were deaf and few of them used sign language interpreters. It was very different from my high school experience, but it didn’t matter to me because I still felt like an odd duck who was black, deaf, and queer (closeted at the time) and I was used to loneliness and depression. In my second year of college, my brother passed away from cancer at age 31. He was my role model because he went to college and got a good job in electronics, but something happened between him and my family so I didn’t get to stay close with him. His death affected me very much and made me realize that I had to make a decision to live for myself and not others. So I went into therapy and made different choices to experience life differently on my own terms. I came out as a queer person. I became a president of Disability Awareness Club. I joined a gospel choir as a musical sign language interpreter. By the time I graduated, I made a decision to go to graduate school instead of going into information technology. I always wanted to go to a deaf school so Gallaudet University was that place for me.

As a master’s student, I had a great two years at Gallaudet University. I had direct communication experience everywhere on campus including classroom and cafeteria. It’s something I didn’t experience every day at school. I didn’t have to struggle as much communication-wise and my socialization experience was fun, but then something unexpected came up. I didn’t feel at home at Gallaudet and I didn’t understand why. Then I realized much later during the doctoral program that it had something to do with my identities as a black deaf graduate student at a predominately white deaf institution that primarily serves undergraduate students. There’s an intersectional component that functions as a barrier for me and it’s a sobering reality considering I had been looking for a cultural home for a very long time. Now at age 41, I realize that home is something I can define for myself and invite others into my space.

4. Have you faced any obstacles or challenges from being deaf and how have you overcome these?

There are always obstacles for me as a deaf person. The major one is communication. The world is hearing-centric so almost everything is designed to serve hearing and speaking and it’s normal. People who are deaf is assumed to be abnormal and there are interventions to make them “normal.” I am expected to accommodate hearing people’s communication comfort level. Another major one is the ideology surrounding disability. There is a misconception that deaf people are educationally challenged and hard to employ, like having a disability is a major impairment to one’s life which is generally not true. If the world makes itself accessible to everyone, disability would be considered part of human variation like height, weight, gender, and skin color, but unfortunately there are physical, institutional, attitudinal, and ideological barriers that make it difficult to create a just world.

So, to overcome these challenges, I have to self-advocate for myself and educate people on the issues. Also, I always look for allies who can support me and educate their peers so I don’t have to do the work all the time. As for the communication barrier, I just tell people that I am deaf and expect them to accommodate me half-way. If they don’t try, I try not to deal with them again. It is not worth the energy.

5. Why did you choose your particular area of specialism?

I chose to study linguistics because of my communication and language experiences in school. As a kid, I loved reading, but I struggled with writing. There’s one teacher in high school who put in extra time to teach me writing and my writing improved a lot. It was her belief that Signing English helped with writing and I believed her. And then when I went to college, I learned more about ASL (American Sign Language) and understood that it was really a language.

A deaf person could be an ASL user and be proficient in English. So, deaf children’s struggle with literacy could be due to instructional methods and literacy exposure, not deafness or sign language. It was my goal to learn linguistics so ASL or any sign language in general doesn’t have to be a culprit behind literacy issues and they shouldn’t be anyway.

6. How have you found being in the academic world as a deaf person?

I love being an academic because I can use the platform to educate the public on certain subjects that they are not familiar with or have been taught differently. There’s power in producing publications and giving presentations in a way that shape their knowledge and behavior and I have the academic credentials that qualifies me as a scholar. But at the same time, being a deaf academic has its challenges. Some people can’t see past my deaf identity because in a way, my disability disqualifies me in their eyes. I have to work especially hard to show that I am, in fact, capable.

My race as a Black man does factor into that as well so being a Black Deaf academic has me dealing with disability and racial barriers in general. With the communication challenge, I have to find sign language interpreters who can work with me at their best. I prefer to have direct communication as much as possible with my colleagues or with my audience, but if they don’t know sign language, then I have to work with the interpreters. If the interpreters know me, my communication style, and my area of study, then our communication will work like magic, but if they don’t, then I will have to change my communication style in a way that benefits the interpreters but at my own expense.

There’s also a challenge of dealing with the subject matters involving marginalized identities and social injustice and that puts me in a position where I have to deal with ignorance and resistance from people who knowingly or unknowingly stand on the side of oppression. I have to navigate these challenges when I have to apply for research grant and share research results.

7. We have seen so many recent social crises over the last year or two. Do you think the Deaf Community does enough / could do more in educating members about the issues and also in actually contributing to the dialogue?

If you mean by deaf organizations, it depends on which organizations. I have seen many organizations doing good things to host webinars on social crises and educate their members about COVID-19 pandemic, Black Lives Matter, and elections, but I also have seen some organizations that are basically silent on the issues. I think the thing we need to remember is that deaf people are people and there’s a wide variety of beliefs, values, and customs that it is not possible to make them monolithic. There’s always a need for the dialogue but there’s a side to take. Alas, such is life.

8. What is your view on the subject of signed language appropriation – hearing people signing songs or teaching: is it a language issue or a cultural issue. Or both?

It is both. I like watching music videos of deaf ASL performers. They make songs come to life with their beautiful translation in sign language and they give us music with their body rhythm, but their views are low compared to hearing signers who are not as proficient or so over the top. It’s almost like mediocrity is preferred by the hearing audience simply because they could relate with hearing performers. Deaf performers have the language, the culture, and the experience to create an artistic experience, but they are underappreciated. I know there are hearing performers that are just as good, but if they don’t have the relationship with the Deaf communities, there’s something wrong with the picture.

They are using the language that represents life for Deaf people, but they exploit it for attention. That always bothers me. As for hearing teachers, it depends on the situation. There are teaching jobs that require certain qualifications that bar deaf people from applying. Deaf teachers should be hired to teach, but if the demand for ASL outpaces the supply of deaf ASL teachers, the positions have to be filled somehow. But when it comes to hearing teachers’ qualifications, that’s where things are different. If they don’t have any connections with the Deaf communities, they are not skilled signers, or they just want to make money, it’s a problem because Deaf communities are not central to ASL teaching or learning. Sign language come from them so they should be included.

9. What is the relationship would you say between the interpreting profession and deaf academics and professionals? Is it mutually supportive? Could more be done to improve it?

It is often the case that having designated interpreters make things easier for deaf academics and professionals at work. The interpreters are familiar with their work, their fields, and their audiences and they can absorb information as they work along with deaf academics and professionals. But that’s a luxury in the hearing-centric world. There should be a way for interpreters to gain more experience and knowledge so they can be effective in their working relationship with deaf academics and professionals. Almost all interpreter programs provide an entry-level training and it is up to the graduates to specialize in certain areas that deaf academics and professionals work in.

At the same time, there’s a greater need for interpreters with specialized knowledge and skills but they are not readily available. It is often the case that deaf academics and professionals put in additional efforts in finding or training interpreters to suit their needs and it is quite an investment so they are protective of them. If the interpreters leave their assignments for whatever reason, the consumers have to do it all over again and it is very taxing. However during the COVID-19 pandemic, video conferencing platforms have made it possible to hire any specialized interpreters anywhere and anytime so the advancement in technology makes this possible overcoming distance and time barriers. Even so, there are financial and attitudinal barriers to consider and not everyone has a luxury to resolve them.

10. Who inspires you and why?

It is impossible to pin down one person who inspires me. I have different people that are the source of my inspiration in each stage of my life. One is my mother. Born in 1940, she has seen and experienced so much as a Black hard of hearing woman and yet she has accomplished by finishing high school, marrying my hearing father, and raising Black Deaf children who have become independent and live on their own terms. She’s passive at times, but when it comes to her children, she fights for them and she will not back down, like I told my 4th grade story about her telling my teachers that they should respect my decision to remain in the deaf program until I was ready. She did fight for me again in high school when I wanted to go fully mainstreamed and the teachers thought I wasn’t ready. Another one is my Deaf sister.

We have a complicated relationship and not always on speaking terms, but I do appreciate learning from her and benefiting from her connections in the Deaf communities when I was a teenager. I had a hard of hearing college friend who moved across the country for college and she inspired me to make the same move for graduate school. For my academic career, one person is Dr. Peter C. Hauser who is a white Deaf man in clinical psychology. Despite the differences in our backgrounds, we do have a lot of things in common so I always turn to him for advice and support.

11. What ways do you think hearing people can be allies to the deaf community? Any DOs and DON’Ts?

They can be allies by practicing cultural humility, deferring to the community, being ready to stand at the frontline, and unpacking their biases and privileges. They also should strive to make the world accessible and constantly remind people on the principle of accessibility and the necessity of mutual respect. What they should not do are to be a savior when we don’t ask for it and to exploit our language and culture for their gain.

12. 3 top tips for deaf people?

1.Self-advocacy is key to everything.

2.Demand accommodation wherever and however you can.

3.Practice self-care.

Sign up to our newsletter for more content like thisLooking for more support? We’ve made it our mission to improve the lives of deaf people everywhere. Check out Deaf Unity’s projects to find out what we can do for you. If you’d like to get in touch, contact us here.